Lecture 4 — Software Engineering for Data Science

Data & Code Management: From Collection to Application

2025-11-06

R packages — Structure, workflow, best practices

Why make an R package?

- Distribute code to others — packaging nudges you to write documentation.

- Enforces conventions (files, names, processes).

- Increases stability via long-term maintenance + testing.

- Improves usability as your function zoo grows.

- Clear API, versioning, and easier onboarding for collaborators.

Setup

You will need (at least) the following packages:

Check your system toolchain:

If not ready: https://r-pkgs.org/setup.html

Demo

(We’ll live-code a tiny package: init → a function → docs → tests → pkgdown.)

Package anatomy

pkgtest/

├─ DESCRIPTION

├─ NAMESPACE # auto-generated by roxygen2

├─ R/ # your exported/internal functions

├─ man/ # *.Rd docs (generated)

├─ tests/testthat/ # unit tests

├─ vignettes/ # long-form docs (optional)

├─ data/ # .rda datasets (optional)

├─ inst/ # e.g., inst/examples/

└─ data-raw/ # raw data + scripts (ignored by build)DESCRIPTION file

DESCRIPTION contains package metadata (authors, description, dependencies, contact, …). Example:

# Plain text (DCF) — shown here for reference

Package: pkgtest

Type: Package

Title: What the Package Does (Title Case)

Version: 0.1.0

Authors@R: person("John", "Doe", email = "john.doe@example.com",

role = c("aut", "cre"))

Maintainer: John Doe <john.doe@example.com>

Description: More about what it does (maybe more than one line).

Use four spaces when indenting paragraphs within the Description.

License: MIT + file LICENSE

Encoding: UTF-8

LazyData: true

URL: https://github.com/ptds2024/pkgtest

BugReports: https://github.com/ptds2024/pkgtest/issues

Roxygen: list(markdown = TRUE)

RoxygenNote: 7.3.1

Suggests:

knitr,

rmarkdown,

testthat (>= 3.0.0)

Config/testthat/edition: 3Tip: usethis::use_description() can scaffold this for you.

Authors and license

Use person() in Authors@R. Common roles:

"cre"= maintainer (creator)"aut"= author (substantial contributions)"ctb"= contributor (smaller contributions)"cph"= copyright holder (institution/corporate)

Choose a license: https://choosealicense.com/licenses/

Dependencies

DESCRIPTION lists what your package needs.

Guidelines:

Importsforfun()used in codes inR/.Dependsfor base R version requirement.Suggestsfor docs, tests, vignettes.- Note: for selective namespace import, use roxygen tags such as:

@importFrom dplyr mutate select.

Documenting your package

- Docs live in

man/as*.Rd(generated). - We generate them with roxygen2 from inline comments.

- Run

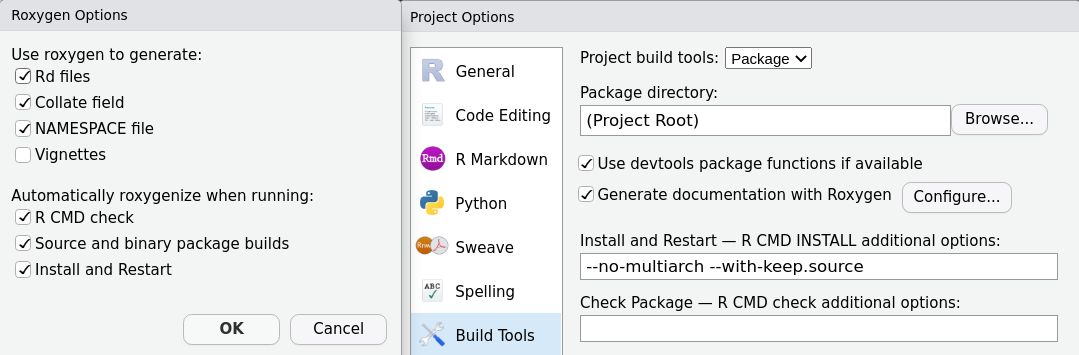

devtools::document()to updateNAMESPACE+man/.

Roxygen basics

Place roxygen just above the function:

Useful tags: @title, @description, @details, @param, @return, @examples, @seealso, @author, @references, @import, @importFrom, @export

Document all user-facing functions; export some of them.

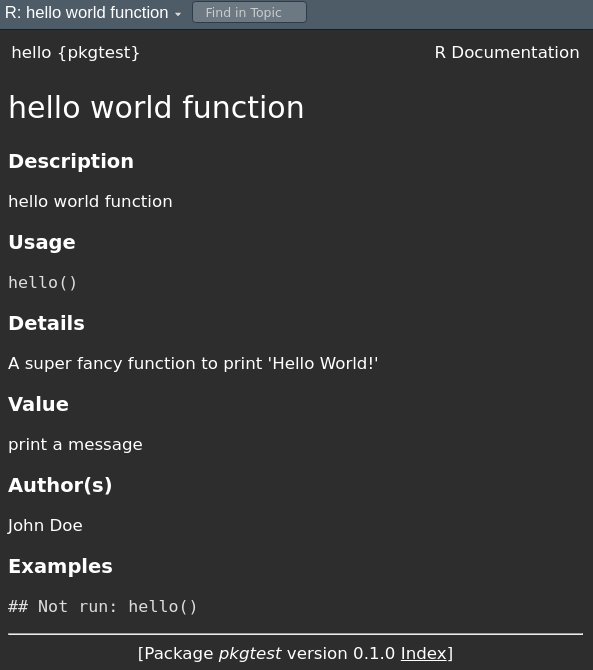

Example: hello() (docs vs. help page)

Import external functions explicitly

Rule: If you call functions from another package, you must import them with roxygen’s @importFrom so NAMESPACE lists them.

It is not sufficient to add pkg::fun() calls in your code.

Otherwise you’ll hit R CMD check NOTES like “no visible global function definition for ‘select’” and users may get runtime errors.

Note: Base R functions (e.g., mean(), lm()) do not need imports.

Do (bare names + explicit imports):

Adding data (binary .rda)

- Place datasets in

data/as.rda. - Use

usethis::use_data()to serialize R objects.

Preserve the origin story (data-raw)

- Keep raw inputs + wrangling scripts under

data-raw/. - Make it reproducible with

usethis::use_data_raw()(auto-adds to.Rbuildignore).

Reference: r-pkgs, “Preserve the origin story of package data”.

Documenting datasets

Two useful tags: @format and @source.

.Rbuildignore

Like .gitignore, but for package builds.

Or maintain manually:

Vignettes

Long-form docs (articles, tutorials) built with R Markdown/Quarto.

Remember to list knitr and rmarkdown under Suggests.

Namespaces (how functions are found)

The namespace controls how R looks up variables: it searches your package namespace, then imports, then base, then the regular search path.

- Generated automatically by roxygen2.

- Use

@exportto expose a function;@importFrom pkg funto bring symbols in.

A toy function to test

In R/reg_coef.R:

#' Compute regression coefficients

#'

#' @param x Design \code{matrix} or vector.

#' @param y Response \code{vector}.

#' @details Uses \link[stats]{lm} then \link[stats]{coef}.

#' @importFrom stats lm coef

#' @seealso \code{\link[stats]{lm}}, \code{\link[stats]{coef}}

#' @example inst/examples/eg_reg_coef.R

#' @export

`%r%` <- function(y, x) {

fit <- lm(y ~ x)

coef(fit)

}“Testing” via examples

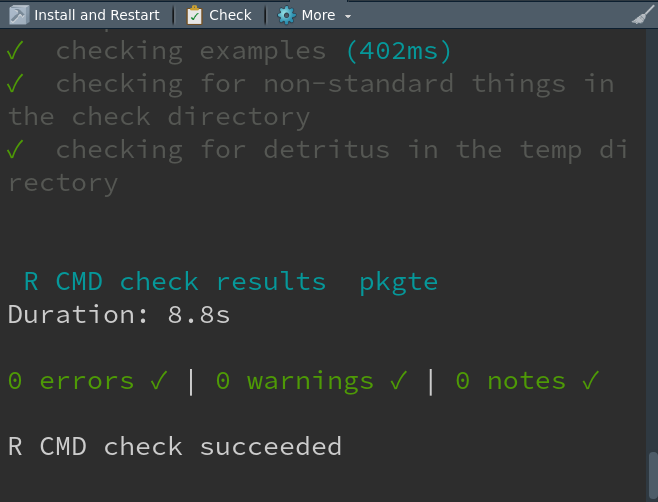

- Examples (in roxygen) are shown to users and run under

R CMD check. - For bigger snippets, place files under

inst/examples/and reference them:

inst/examples/eg_reg_coef.R:

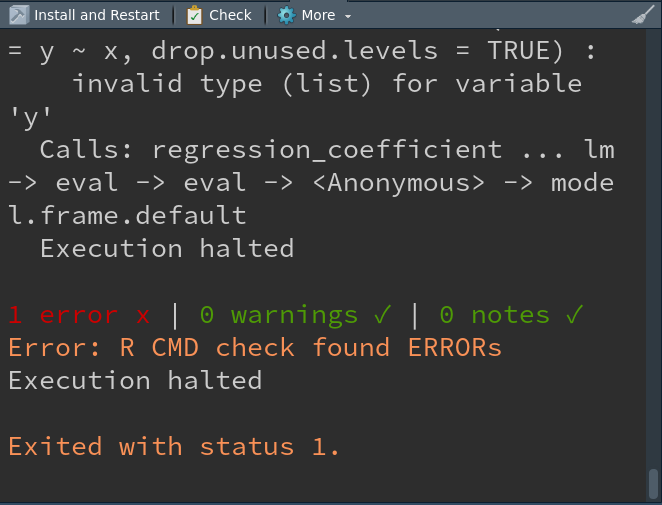

What happens on check?

Intentional mistake (to see failure)

If inst/examples/eg_reg_coef.R contains:

You’ll get a failing check:

Testing with testthat

Examples are for users; tests are for you (broader, automated).

“Whenever you are tempted to type something into a print statement or a debugger expression, write it as a test instead.” — Martin Fowler

testthat structure

- Expectation: a single check (

expect_*()). - Test: one or more expectations (

test_that()). - Test file: one or more tests (e.g.,

tests/testthat/test_reg_coef.R).

Example:

Continuous Integration (GitHub Actions)

Run checks on multiple R versions/OS on every push/PR:

More examples: https://github.com/r-lib/actions/tree/master/examples

Keep CI within budget (class org)

- We have only 3000 free Actions minutes/month for the class org.

- Prefer public repos (or self-hosted runners) → no Actions minutes used.

- For private repos, test on your personal repo first; then fork to class org.

- Trigger CI on PRs/manual runs and use

pathsfilters:

Keep CI within budget (class org)

- Skip manually CI with

[skip ci]:

Code coverage (nice enhancement)

Measure what your tests execute:

Aim for high, but don’t chase 100% blindly — test the behavior that matters.

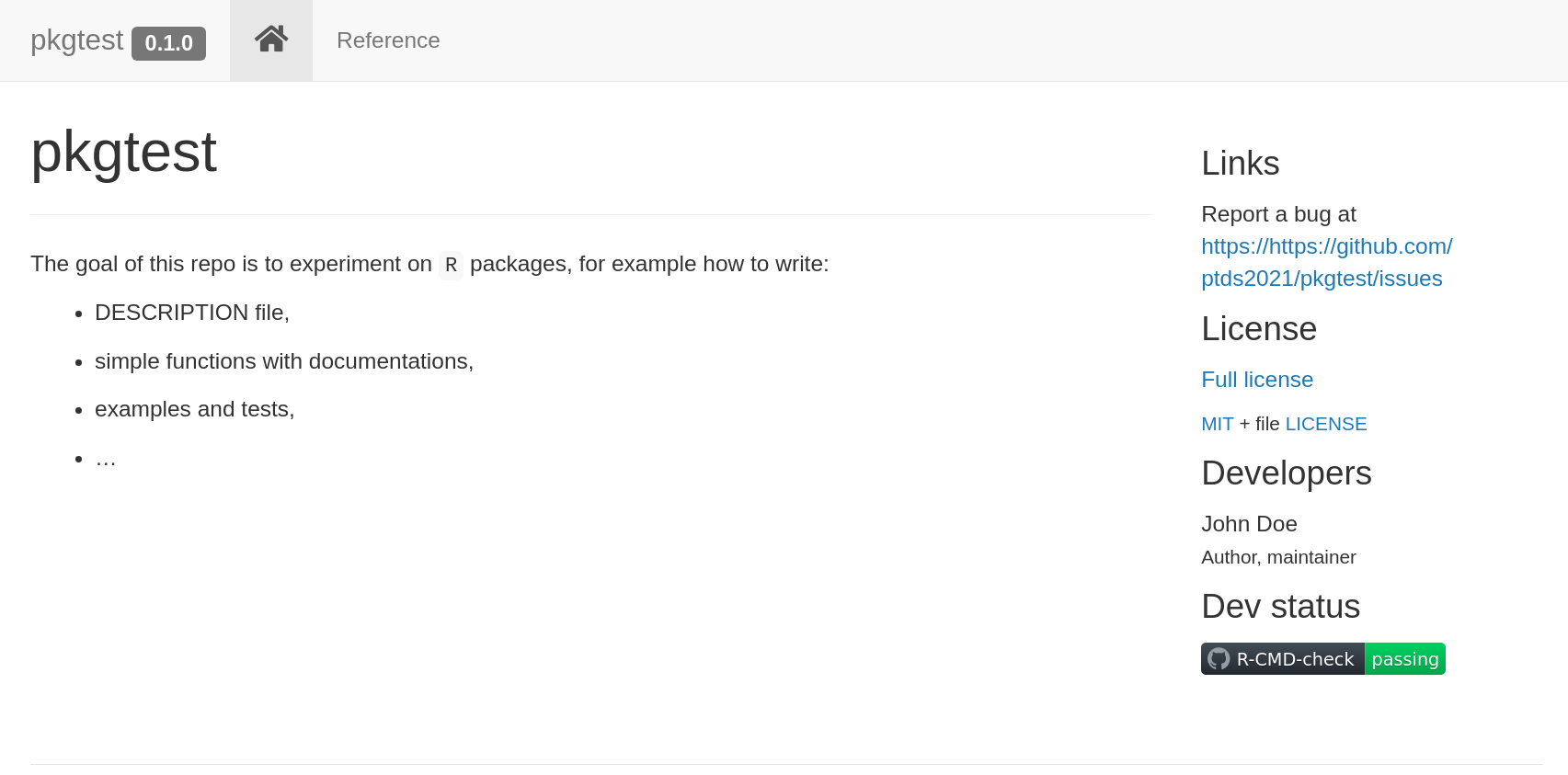

pkgdown (package website)

Quickly create a website from your docs/vignettes:

Example site preview

Release checklist (SemVer)

- Update

NEWS.md(usethis::use_news_md()). - Bump version in

DESCRIPTION(e.g.,0.1.0→0.2.0for features). devtools::check()clean locally (no ERROR/WARNING/NOTE).- All CI green; coverage reasonable.

- Rebuild site; tag the release; write a short changelog.

- Consider CRAN policies if submitting (e.g.,

R CMD check --as-cran).

Install from GitHub (user)

For users (install the released tag):

Note: Building from source may require Rtools (Windows) or Xcode CLT (macOS).

Typical workflow (big picture)

usethis::create_package("pkgtest")- Write a function in

R/ - Add roxygen docs →

devtools::document() - Add tests →

usethis::use_testthat()→ writetests/testthat/ - Check →

devtools::check() - CI →

usethis::use_github_action_check_standard() - Site →

usethis::use_pkgdown()→pkgdown::build_site() - Release checklist and version bump (SemVer)

Tips & helpers (usethis)

Resources

- Code shown here: https://github.com/ptds2024/pkgtest

- R Packages (2e): https://r-pkgs.org/

- Writing R Extensions: https://cran.r-project.org/doc/manuals/r-release/R-exts.html

- Book chapter: An Introduction to Statistical Programming Methods with R — Packages section: https://smac-group.github.io/ds/section-r-packages.html

Creating a Python Library

Why a Python library (R parallels)

- Distribute code, enforce conventions, improve stability.

- R:

DESCRIPTION,NAMESPACE, roxygen, testthat, pkgdown

- Py:

setup.py/wheel,__init__.py, docstrings, pytest, MkDocs

Set up a virtual environment (VS Code)

- VS Code → “Python: Select Interpreter” → pick

./venv

Minimal structure (parallel to R package anatomy)

pypkg/ # ← package root (like R pkg root)

├─ setup.py # ← like DESCRIPTION (+ build recipe)

├─ MANIFEST.in # ← include data files (like .Rbuildignore inverse)

├─ README.md

├─ pypkg/ # ← source (like R/ folder)

│ ├─ __init__.py # ← public API (like NAMESPACE role)

│ ├─ hello.py # ← hello()

│ ├─ regression.py # ← reg_coef()

│ ├─ data.py # ← load_snipes()

│ └─ data/

│ └─ snipes.csv # ← packaged dataset

├─ examples/

│ └─ eg_reg_coef.py # ← like inst/examples/...

├─ tests/ # ← pytest (like tests/testthat)

│ ├─ test_hello.py

│ ├─ test_regression.py

│ └─ test_data.py

We need to create these files step-by-step.

Create your project directory (Terminal basics)

Open your terminal (VS Code: View → Terminal) and create a folder for your Python library.

hello() (R: the “Hello, world!” slide)

pypkg/hello.py

pypkg/__init__.py — expose the public API (like exporting in NAMESPACE)

Build a wheel (R: R CMD build)

setup.py (simple & minimal)

Build:

Install & try:

Dataset: snipes (R: data/snipes.rda + data-raw)

Ship the CSV and provide a loader (no pandas required).

pypkg/data.py

from importlib import resources

import csv, io

from typing import List, Dict

def load_snipes() -> List[Dict[str, str]]:

"""Load the bundled 'snipes' dataset (list of dict rows)."""

with resources.files("pypkg.data").joinpath("snipes.csv").open("rb") as fh:

text = io.TextIOWrapper(fh, encoding="utf-8")

return list(csv.DictReader(text))MANIFEST.in — include data in the wheel

R parallel:

use_data()writesdata/*.rda; here we ship a CSV + loader.

Preserve the origin story (R: data-raw/)

Keep raw files & scripts outside the wheel (tracked in Git):

R parallel:

usethis::use_data_raw()+.Rbuildignore; Py: keepdata_raw/out ofMANIFEST.in.

Documenting dataset (R: @format, @source)

Use the loader’s docstring:

MkDocs (later) will render this automatically.

Regression coefficients (R: %r% with stats::lm)

Implement a tiny OLS with NumPy (no heavy deps).

pypkg/regression.py

from typing import Iterable, Tuple

import numpy as np

def reg_coef(y: Iterable[float], x: Iterable[float]) -> Tuple[float, float]:

"""

Compute OLS coefficients for y ~ 1 + x.

Returns

-------

(intercept, slope)

"""

y = np.asarray(y, dtype=float).reshape(-1, 1)

x = np.asarray(x, dtype=float).reshape(-1, 1)

if y.shape[0] != x.shape[0]:

raise ValueError("x and y must have the same length")

X = np.c_[np.ones_like(x), x]

beta, *_ = np.linalg.lstsq(X, y, rcond=None)

b0, b1 = beta.ravel().tolist()

return b0, b1R parallel: returns

coef(lm(y ~ x)).

Example script (R: inst/examples/eg_reg_coef.R)

examples/eg_reg_coef.py

Run:

Update public API (R: NAMESPACE)

pypkg/__init__.py — expose the public API (like exporting in NAMESPACE)

Re-Build a wheel (R: R CMD build)

setup.py (simple & minimal)

from setuptools import setup, find_packages

setup(

name="pypkg",

version="0.1.0",

description="Tiny demo library",

author="Your Name",

packages=find_packages(include=["pypkg", "pypkg.*"]),

install_requires=["numpy>=1.26"],

include_package_data=True, # needed with MANIFEST.in

python_requires=">=3.9",

)Build:

Install & try:

Tests (R: testthat)

Install pytest (already done) and add three tests.

tests/test_hello.py

tests/test_regression.py

Run:

“Explicit imports” (R: @importFrom rule)

- In R, bare names require

@importFrom pkg fun. - In Python, prefer explicit imports at the top:

Clear imports → fewer undefined symbols, better tests & CI.

CI (GitHub Actions) — lite & budget-friendly

.github/workflows/python-ci.yml

name: Python CI (lite)

on:

pull_request:

paths:

- "pypkg/**"

- "tests/**"

- "setup.py"

- "MANIFEST.in"

- ".github/workflows/**"

workflow_dispatch:

concurrency:

group: ${{ github.workflow }}-${{ github.ref }}

cancel-in-progress: true

jobs:

test:

if: "!contains(github.event.head_commit.message, '[skip ci]')"

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- uses: actions/setup-python@v5

with: { python-version: "3.11", cache: "pip" }

- run: python -m pip install -U pip

- run: pip install -e . pytest

- run: pytest -qDocs (R: pkgdown) — optional but nice

1) Install: Add MkDocs later to auto-render docstrings:

2) Configure

Docs

3) Write docs

Create docs/index.md (overview/quickstart) and docs/api.md for the API.

docs/index.md (example)

docs/api.md (auto API from docstrings)

4) Preview & build

Release & SemVer (same rule as R slides)

0.1.0→ new features: MINOR; bugfix: PATCH; breaking: MAJOR.- Tag:

git tag v0.1.0 && git push --tags - Build wheel, test in a fresh venv, then (optionally) TestPyPI → PyPI with

twine.

Install from GitHub

For users (install from GitHub):

Quick recap (R ↔︎ Py)

- hello() → printed message ⟷ returns/prints in Python.

- snipes dataset →

load_snipes()with packaged CSV. - regression coefficients →

reg_coef()via NumPy OLS. - examples →

examples/eg_reg_coef.py(likeinst/examples). - tests →

pytest(liketestthat). - CI → Actions (lite).

- docs/release → optional MkDocs, SemVer tags + wheel upload.

When should you create a library?

- Rule of Three: you’ve copied the same functions across ≥ 3 projects.

- Audience > you: teammates/students need to reuse your code.

- Stable core idea: function names/arguments won’t change every week.

- Testing matters: you’re willing to add automated tests (testthat/pytest).

- Versioning matters: you want SemVer to communicate changes.

- Docs exist: you can write a README and minimal usage examples (vignette/doc page).

- Multiple environments: others will run it on different machines/OS.

When not (yet)

- One-off notebook/report: no planned reuse.

- Spike/prototype: API and data shapes still change daily.

- Entangled secrets/paths: credentials or local file paths mixed with logic.

- Huge assets: gigabytes of data/binaries—ship loaders, not raw assets.

- No maintainer bandwidth: can’t commit to fixes/docs/release bumps.

Heuristic: if you’d hesitate to fix a bug reported by someone else, don’t package yet.

Object-Oriented Programming

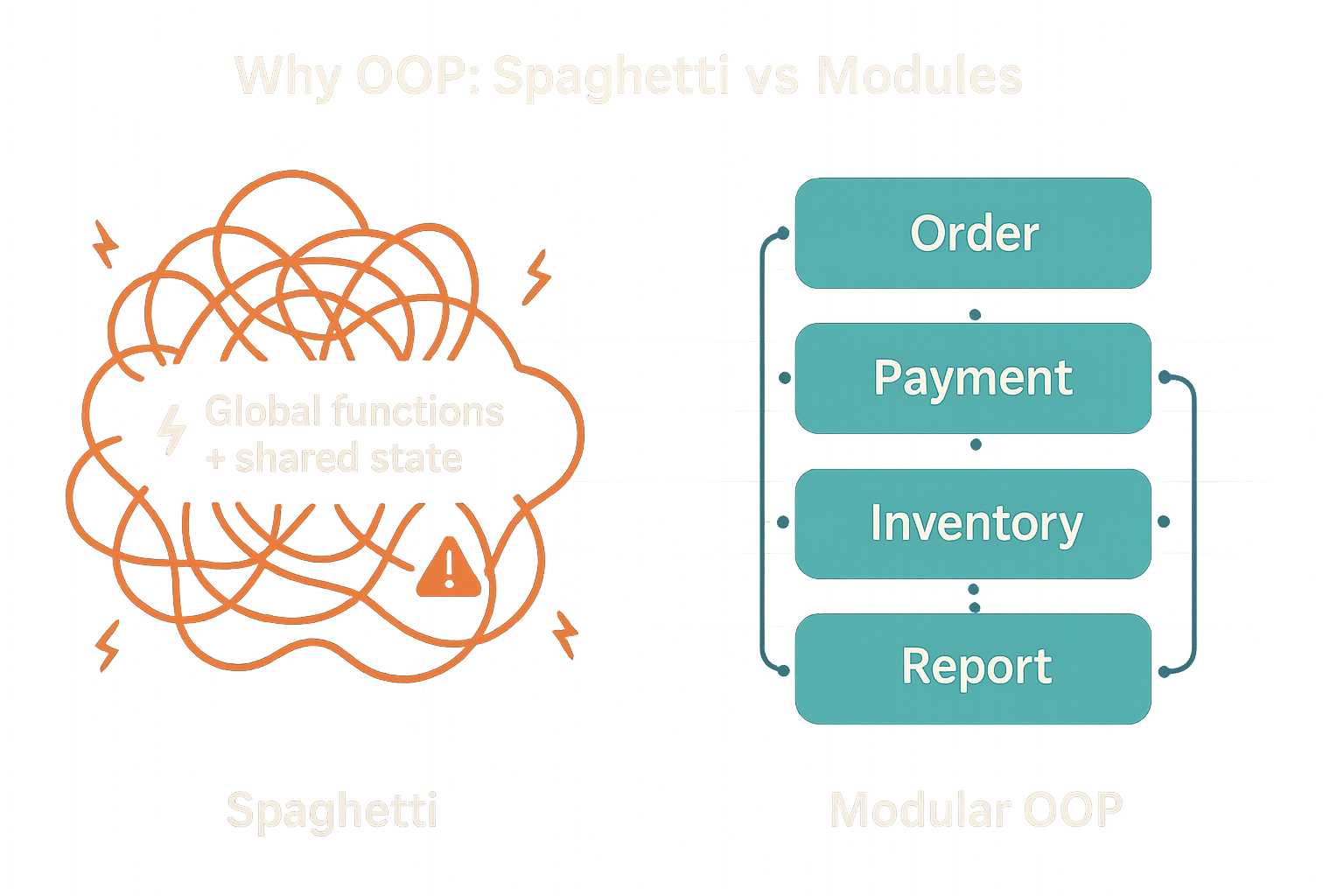

Why OOP?

- Tame complexity. Large codebases drift into “spaghetti code” when everything touches everything. OOP groups data + behavior into cohesive modules (classes) with clear interfaces.

- Reuse & extension. Add new features by creating new classes or methods—without rewriting callers (polymorphism).

- Safer changes. Internals can evolve behind the interface (encapsulation), reducing ripple effects and regressions.

Note

Context: The “spaghetti code” idea is often cited in post-mortems of complex systems (e.g., discussions around large automotive software stacks). Clear module boundaries and interfaces are a first line of defense, (see Toyota 2013 case study)

Part I — R Functions & S3 OOP

Function

“Everything is a function call”

- A function has three components: arguments, a body, and an environment.

- Signalling conditions: errors (severe), warnings (mild), messages (informative).

- Lexical scoping: dynamic lookup & name masking.

- Environments: current, global, empty, execution, package.

- Composition via nesting or piping (

|>).

Signalling conditions

Lexical scoping

S3 OOP system

- Object-oriented programming (OOP) is a popular programming paradigm.

- The type of an object is a class and a function implemented for a specific class is a method.

- Polymorphism: function interface is separated from its implementation; behavior depends on class.

- Encapsulation: object interface is separated from its internal structure; users don’t need to worry about details. Encapsulation helps avoid spaghetti code.

Rhas several OOP systems: S3, S4, R6, …- S3 is the first R OOP system; it is informal (easy to modify) and widespread.

Minimal S3 example

# Minimal S3 example: generic + methods

area <- function(x, ...) UseMethod("area") # generic

# constructor for a 'circle'

new_circle <- function(radius) structure(list(radius = radius), class = "circle")

area.circle <- function(x, ...) pi * x$radius^2

# constructor for a 'rectangle'

new_rectangle <- function(w, h) structure(list(w = w, h = h), class = "rectangle")

area.rectangle <- function(x, ...) x$w * x$h

c1 <- new_circle(2)

r1 <- new_rectangle(3, 4)

area(c1); area(r1)Why OOP?

- Uniform interfaces: one verb (e.g.,

summary(),plot()) works across many data types. - Separation of concerns: analyses call verbs; classes handle how.

- Extensibility: you can add behavior for new data types without touching old code.

- Safer refactoring: callers don’t change; class-specific methods evolve independently.

- Discoverability: “What happens if I call

summary()on this object?” → predictable, documented.

In R, this is powered by S3: a lightweight dispatch system that maps a generic (like

summary) to a method (likesummary.lm) based on the object’s class.

S3 OOP — Motivation

- Polymorphism: same function name, different behavior by object class.

- Lightweight encapsulation: use interfaces, not internals.

- Informal & flexible (no strict class declarations).

Polymorphism example

Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

4.0 12.0 15.0 15.4 19.0 25.0

Call:

lm(formula = cars$speed ~ cars$dist)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-7.5293 -2.1550 0.3615 2.4377 6.4179

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 8.28391 0.87438 9.474 1.44e-12 ***

cars$dist 0.16557 0.01749 9.464 1.49e-12 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 3.156 on 48 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.6511, Adjusted R-squared: 0.6438

F-statistic: 89.57 on 1 and 48 DF, p-value: 1.49e-12What is happening? (dispatch)

summary.double

summary.numeric

=> summary.default=> summary.lm

* summary.default[1] "numeric"[1] "lm"*method exists;=>method selected.

Peeking at generics (R)

function (object, ...)

UseMethod("summary")

<bytecode: 0x5568d595b0c8>

<environment: namespace:base>

1 function (object, ..., digits, quantile.type = 7)

2 {

3 if (is.factor(object))

4 return(summary.factor(object, ...))

5 else if (is.matrix(object)) {

6 if (missing(digits))

1 function (object, correlation = FALSE, symbolic.cor = FALSE,

2 ...)

3 {

4 z <- object

5 p <- z$rank

6 rdf <- z$df.residual ... — forwarding extra arguments

- Useful for generics and passing options forward.

Write a generic + methods (R, S3)

Check the dispatch & implicit class

Inheritance (multiple classes)

If a method isn’t found for the 1st class, R tries the next, and so on.

Create your own S3 class (quick way)

Create your own S3 class (neater)

Create your own S3 class with a constructor

Caution

How can we make this constructor more robust?

Validators

- More complicated class require more complicated checks for validity.

- Rather than making constructor complicated, we can define a validator function for the checks.

Extending an existing generic (with care)

New plot for class pixel

Forwarding extra options with ...

To go further (R)

- An Introduction to Statistical Programming Methods with R — Functions.

- Advanced R (Hadley Wickham), Ch. 6–8 (functions), 12–16 (OOP: S3, S4, R6).

Part II — Python OOP

Why OOP in Python?

- Class-based OOP: define classes (blueprints) and create instances (houses).

- Encapsulation: group data (attributes) with behavior (methods).

- Inheritance: share and extend behavior (code reuse).

- Polymorphism: same method name, different behaviors across types.

- Generic functions with

@singledispatchprovide an R-S3-like feel when helpful.

Classes & instances

classdefines a new type.__init__is the constructor (like R’snew_*()).selfis the instance being operated on. It’s just a naming convention (not a keyword), but always the first parameter of instance methods.

Encapsulation (group data + behavior)

Inheritance & overriding

Polymorphism (same message, different response)

Generic functions with @singledispatch

from functools import singledispatch

import statistics as stats

@singledispatch

def describe(x):

return f"Generic object of type {type(x).__name__}"

@describe.register(list)

def _(x: list):

return {"len": len(x), "mean": stats.mean(x)}

class LinReg:

def __init__(self, coef, intercept): self.coef, self.intercept = coef, intercept

@describe.register(LinReg)

def _(m: LinReg):

return {"coef": m.coef, "intercept": m.intercept}

describe([1,2,3]), describe(LinReg([0.5], 2.0))Note

Rule of thumb in Python:

Use class methods when you control the class design.

Use

@singledispatchwhen you want an external, pluggable generic (like S3) that different modules can extend without modifying the original class.

Composition & duck typing

- Interfaces by behavior: “if it quacks like a duck…”

- Prefer composition when inheritance isn’t needed.

savedoesn’t care what the writer is—only that it has.write().

- You can plug in a new writer (CSV, YAML, DB, HTTP…) without touching save.

Pass in behavior (composition), don’t inherit it, when all you need is a capability.

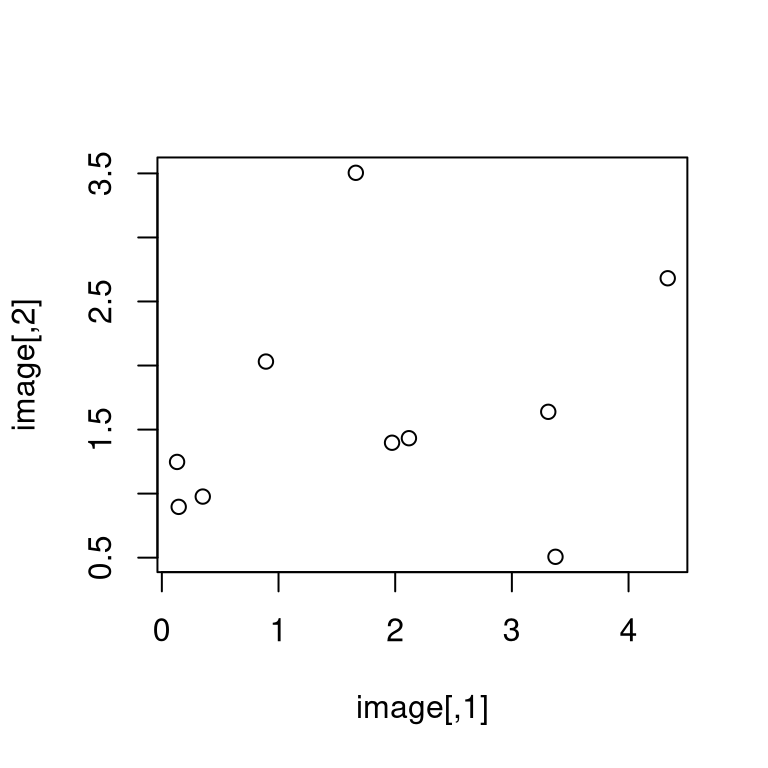

A tiny “generic plot” (analogy to R’s plot())

import numpy as np, matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from functools import singledispatch

class Pixel:

def __init__(self, data): self.data = np.array(data)

@singledispatch

def plot(obj):

raise TypeError(f"Don't know how to plot {type(obj).__name__}")

@plot.register

def _(obj: Pixel):

plt.imshow(obj.data); plt.title("Pixel"); plt.show()

rng = np.random.default_rng(123)

image = rng.gamma(shape=2.0, scale=1.0, size=(10,10))

px = Pixel(image)

plot(px)To go further (Python)

- Python tutorial on classes (docs.python.org)

functools.singledispatchfor generic functionsinspectfor introspection,abcfor abstract base classes

Bridges — R S3 ↔︎ Python OOP

Generic function

- R:

summary(x)→summary.<class>via S3 dispatch. - Python:

@singledispatchpicks implementation by type.

- R:

Class identity

- R S3:

class(x)is an attribute; can be a vector (ordered inheritance). - Python:

type(x)is the class; inheritance via MRO chain.

- R S3:

Extensibility

- R: add

generic.class <- function(x, ...) {}for known generics (mind...). - Python:

@generic.register(Type)or subclass and override methods.

- R: add

Scoping / environments vs namespaces

- R: function environments, lexical scoping.

- Python: LEGB (Local–Enclosing–Global–Builtins).

Varargs

- R:

...↔︎ Python:*args, **kwargs.

- R:

Recap

- OOP gives you uniform verbs, decoupled implementations, and extensibility.

- In R, S3 makes this lightweight and idiomatic (

summary,plot,coef, …). - In Python, classes +

@singledispatchcover both class methods and generic functions.

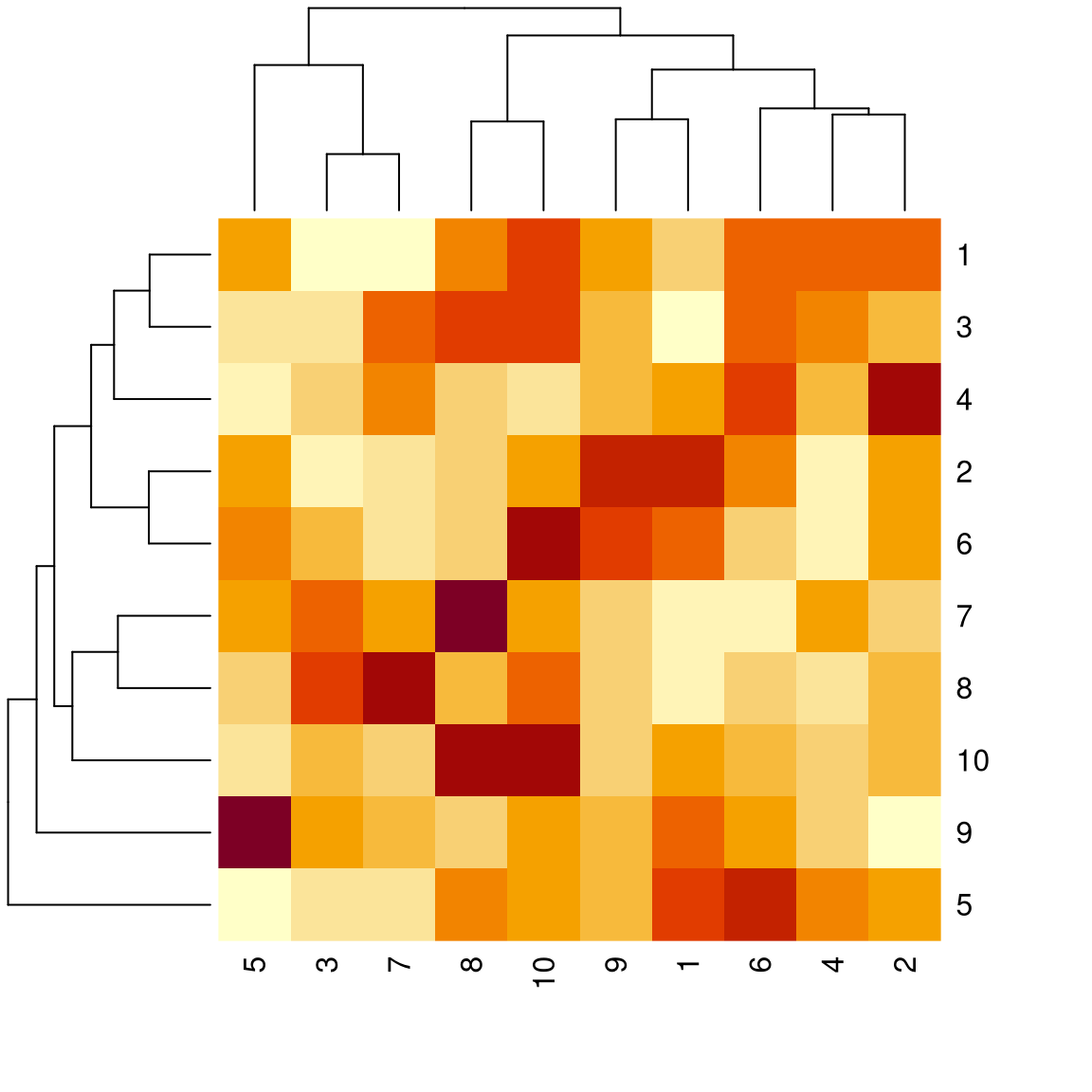

Case study (R, S3): a tiny smoother model

Goal: Create a simple “model” object that computes a moving-average fit and immediately works with summary() and plot() via S3.

# Tiny moving average helper (base R)

movavg <- function(z, k = 5) {

stopifnot(k %% 2 == 1, k >= 3)

n <- length(z); out <- rep(NA_real_, n); h <- k %/% 2

for (i in (1 + h):(n - h)) out[i] <- mean(z[(i - h):(i + h)])

out

}

# Constructor returning an S3 object of class "my_smooth"

my_smooth <- function(x, y, k = 5) {

stopifnot(length(x) == length(y))

o <- order(x); x <- x[o]; y <- y[o]

structure(

list(x = x, y = y, k = k, fitted = movavg(y, k), call = match.call()),

class = "my_smooth"

)

}Case study (R, S3): methods + usage

# Summary method

summary.my_smooth <- function(object, ...) {

res <- object$y - object$fitted

c(n = length(object$y),

k = object$k,

mse = mean(res^2, na.rm = TRUE))

}

# Plot method

plot.my_smooth <- function(x, ..., col_points = "grey40", pch = 19) {

plot(x$x, x$y, col = col_points, pch = pch,

xlab = "x", ylab = "y", main = "my_smooth fit", ...)

lines(x$x, x$fitted, lwd = 2)

legend("topleft", bty = "n", legend = paste0("k = ", x$k))

}

# Fit on 'cars' and use generic verbs

m <- my_smooth(cars$dist, cars$speed, k = 5)

summary(m)Case study (R, S3): what dispatch did

Takeaways

- We created a new class (

"my_smooth") with a tiny constructor. - By adding

summary.my_smoothandplot.my_smooth, existing verbs just work. - Analyses call generic verbs; class authors decide the behavior.

Case study (Python): the same idea with classes + @singledispatch

Goal: Mirror the R idea: a small smoother class, plus generic summarize() and plot() that dispatch on type.

import numpy as np

class Smooth:

def __init__(self, x, y, k=5):

assert k % 2 == 1 and k >= 3

idx = np.argsort(x)

self.x = np.array(x)[idx]

self.y = np.array(y)[idx]

self.k = k

self.fitted = self._movavg(self.y, k)

def _movavg(self, z, k):

n = len(z); out = np.full(n, np.nan); h = k // 2

for i in range(h, n - h):

out[i] = np.mean(z[i - h:i + h + 1])

return outCase study (Python): generic functions + usage

from functools import singledispatch

import numpy as np, matplotlib.pyplot as plt

@singledispatch

def summarize(obj):

raise TypeError(f"No summarize() for {type(obj).__name__}")

@summarize.register

def _(obj: Smooth):

res = obj.y - obj.fitted

return {"n": len(obj.y), "k": obj.k, "mse": float(np.nanmean(res**2))}

@singledispatch

def plot(obj):

raise TypeError(f"No plot() for {type(obj).__name__}")

@plot.register

def _(obj: Smooth):

plt.scatter(obj.x, obj.y, s=15)

plt.plot(obj.x, obj.fitted, linewidth=2)

plt.title(f"Smooth (k={obj.k})")

plt.xlabel("x"); plt.ylabel("y"); plt.show()

# Example with 'cars'-like data (replace with real arrays in class)

dist = [d for d in range(2, 122, 2)]

rng = np.random.default_rng(123)

speed = (0.3*np.array(dist) + rng.normal(0, 3, len(dist))).tolist()

m = Smooth(dist, speed, k=5)

summarize(m), plot(m)Case study

Same verb, different types

- R:

summary(m)→ findssummary.my_smooth. - Python:

summarize(m)→@singledispatchpicks theSmoothimplementation.

- R:

Extensibility

Add another class (e.g.,

my_tree) and define just two methods:- R:

summary.my_tree(),plot.my_tree() - Python:

@summarize.register(MyTree),@plot.register(MyTree)

- R:

Separation of concerns

- Analysts keep calling the same verbs; class authors evolve internals safely.

OOP Exercise in R

Setup (given): you have my_smooth(x, y, k) (constructor) with

summary.my_smooth() and plot.my_smooth() from the case study.

A. Create and use an object 1) Build three models with different windows: k = 3, k = 7, k = 11.

2) Call summary() on each.

3) In 1–2 lines: which k fits best (lower MSE) on your data?

B. Add a tiny exporter Add an S3 method to convert your object to a simple list:

Then run: d <- as.list(m7); names(d) Why is exporting to a plain list handy (think: saving, APIs, tests)?

OOP Exercise in R (continued)

C. Make a simple prediction Add a predict() S3 method using linear interpolation along the fitted curve:

Try: predict(m7, c(10, 20, 30)) and print the results.

D. Plot (optional) Plot your three models and briefly describe how increasing k changes smoothness:

OOP Exercise in Python

Setup (given): you have Smooth(x, y, k=5) from the case study, plus:

A. Create and use an object

- Make a

Smoothwithk = 3,k = 7,k = 11. - Call

summarize()on each. - In 1–2 lines: which

kfits best (lower MSE) on your data?

B. Add a tiny method Add this method inside Smooth:

Then do: d = m.to_dict() and print the keys. Why is this useful?

OOP Exercise in Python (continued)

C. Make a simple prediction Add inside Smooth:

Try predict([10, 20, 30]) and print the results.

D. Plot (optional) Make a function:

Plot your three models; in 1–2 lines, say how increasing k changes smoothness.

Functional Programming

Functional programming

A paradigm emphasizing pure functions (no side effects), immutability, and declarative style.

Benefits: maintainable, predictable, and scalable (parallelizable) code.

Key concepts:

- Pure function: same output for same input; no side effects.

- First-class functions: can be passed, returned, stored.

- Higher-order functions: take/return functions.

Pure function

- A pure function always produces the same output for the same input.

- Is

rnorma pure function?

Pure function (continued)

- Same explicit call but different internal RNG state →

rnormis not pure.

First-class functions — pass as argument

First-class functions — returning a function

- See Function factories.

Function operators / higher-order

- See Function operators.

From for loops to functionals — squares (R)

From for loops to functionals — sum

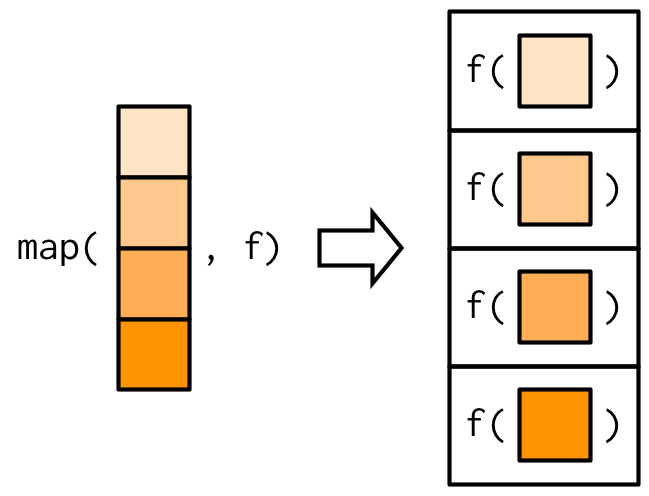

purrr::map() (R)

Returning atomic vectors

map/lapplyreturn alist; sometimes you want an atomic vector.- Use

map_lgl(),map_int(),map_dbl(),map_chr()or basesapply/vapply.

Inline anonymous functions

There are situations where the function you want to pass does not exist yet. Use an inline anonymous function (aka lambda).

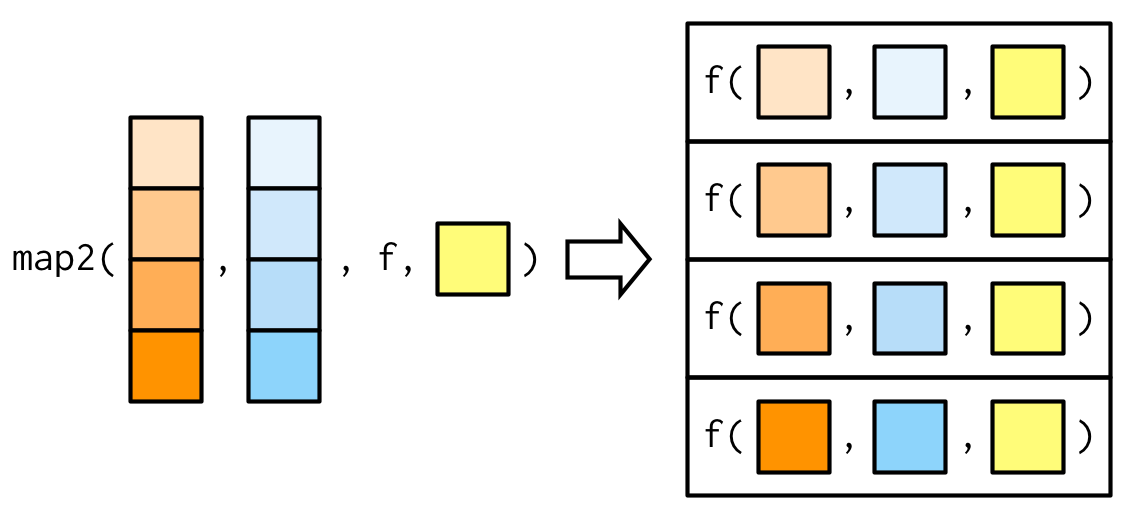

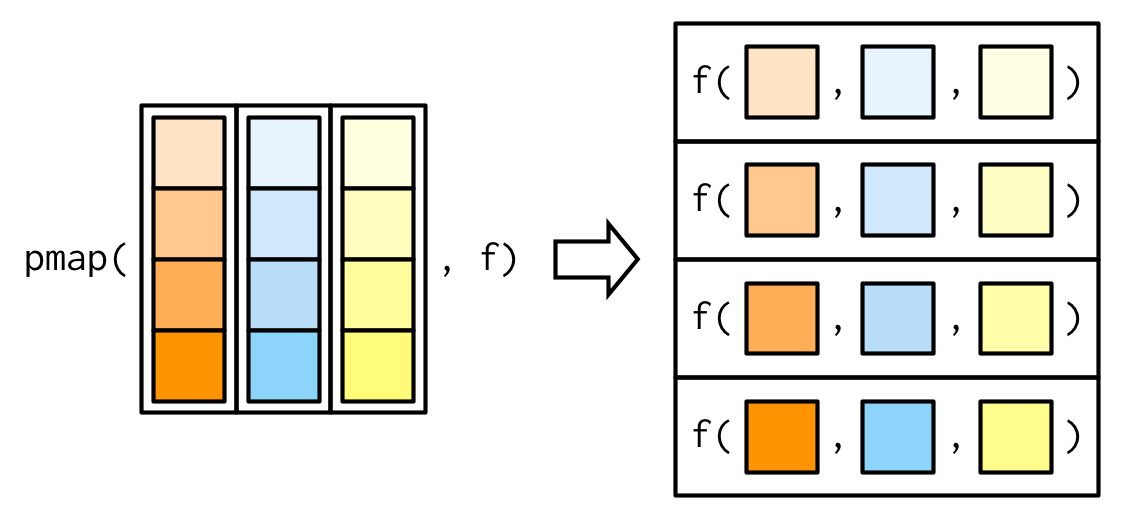

Variants to purrr::map()

pmap generalization (R)

Variants to sapply (R)

mapplygeneralizessapplyto many inputs.Mapvectorizes over all arguments (no extra non-vectorized input allowed).

outer product (R)

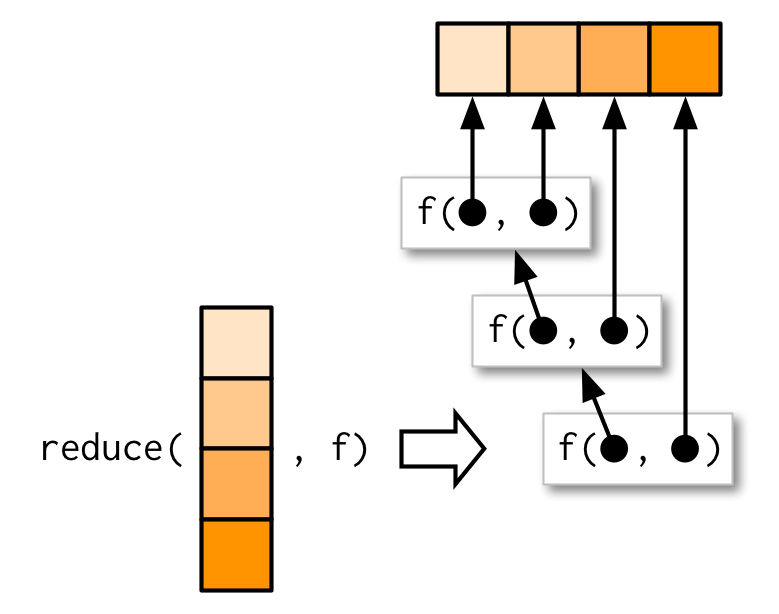

Common higher-order functions in FP (R)

- Higher-order = take/return functions.

Reduceapplies a binary function iteratively to elements of a vector.

R’s vectorization

Vectorizing a function (R): pitfall then fix

Vectorizing a function (R): Vectorize

Vectorizing a function (R): ifelse

Parallelism (R)

- Benefits of FP include scalability and parallelism.

- Many problems are embarrassingly parallel.

parallelships with R and offers parallelized*applyvariants.

- This is the total number of threads (Hyper-Threading), not physical cores.

Forking with mclapply (R)

Forking with mclapply (R)

Socket cluster with parLapply (R)

Socket cluster with parLapply (R)

Python counterparts

- Python is multi-paradigm. It supports functional programming (FP) alongside OOP and imperative styles.

- Functional tools:

map/filter, comprehensions,itertools,functools.reduce/partial/lru_cache. - Vectorization is via NumPy (ufuncs). Parallelism via

concurrent.futures/multiprocessing. - Defaults are eager at definition time (vs. R’s lazy promises); use the

Nonepattern for dynamic defaults.

To go further

- R: Advanced R — Functionals, Function factories, Function operators.

- R:

purrrcheatsheet. - R: Loop Functions & Parallel Computation in R Programming for Data Science.

HEC Lausanne · Business Analytics · Thu 9:00–12:00